Peltier was active in the American Indian Movement, which began in the 1960s as a local organization in Minneapolis.

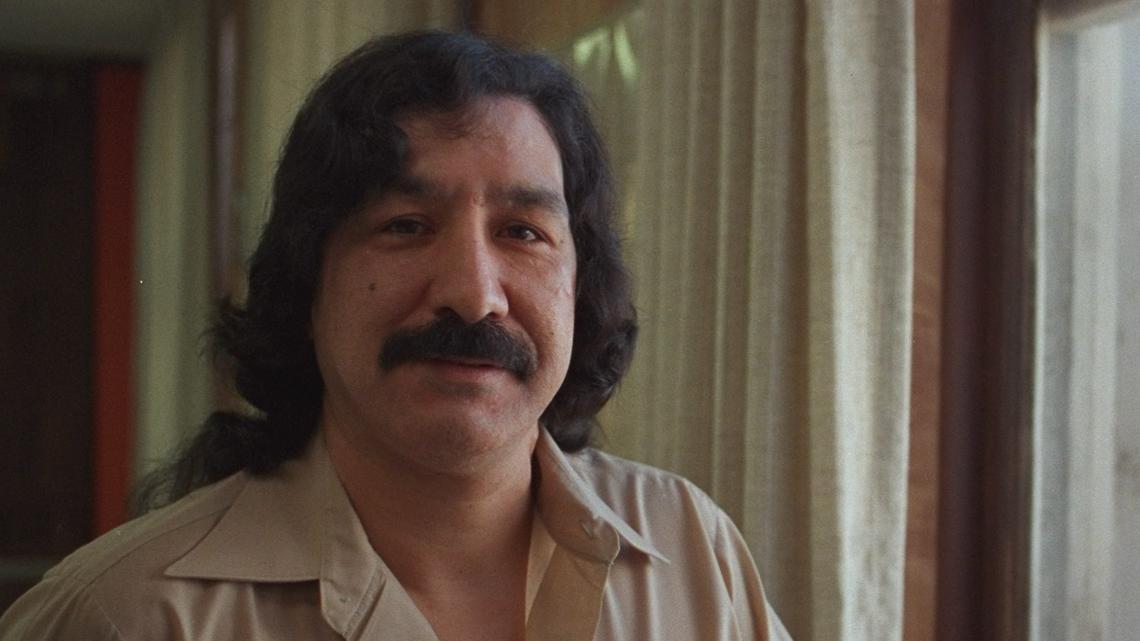

WASHINGTON — Just moments before leaving office, President Joe Biden commuted the life sentence of Indigenous activist Leonard Peltier, who was convicted in the 1975 killings of two FBI agents.

Peltier was denied parole as recently as July and wasn’t eligible for parole again until 2026. He was serving life in prison for the killings during a standoff on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota. He will transition to home confinement, Biden said in a statement.

“Today is victory day,” said Mike Forcia. He’s the longtime chairman of the American Indian Movement (AIM) that was formed in Minneapolis back in 1968. Peltier was also part of the group.

Forcia says Indigenous people were fighting against police brutality and poverty and fighting for treating rights and reform when the group got started.

“If you mention the American Indian Movement, people automatically think Minneapolis because this is the place it was born, but we have so much work left to do,” said Forcia.

He’s joined by a new generation of leaders including Rachel Dionne-Thunder. She helps lead the group Indigenous Protector Movement. Her father was also a part of AIM and advocated for Peltier’s release. Dionne-Thunder marched to D.C. for the same reason two years ago.

“Today, with Leonard Peltier’s release, we see the culmination of decades of advocacy, of prayers, and of work, dedication and sacrifice” said Dionne-Thunder.

Peltier’s release has drawn fierce opposition from law enforcement, but for Native Americans, his arrest represented struggles with the federal government, particularly on Indigenous lands.

“That if you resist, this is what will happen to you, that’s the message they were trying to send and obviously that didn’t work because we’re here today,” said Dionne-Thunder.

Forcia points to a community clinic and Little Hearth housing as their work in Minneapolis continues.

“It means my dad finally gets to go home,” said Chauncy Peltier, who was 10 when his father was locked up. “One of the biggest rights violation cases in history and one of the longest-held political prisoners in the United States. And he gets to go home finally. Man, I can’t explain how I feel.”

Peltier’s tribe, the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa, has a home ready for him on the Turtle Mountain Indian Reservation in Belcourt, North Dakota, his son said.

Bureau of Prisons spokesperson Emery Nelson said Peltier remained incarcerated Monday at USP Coleman, a high-security prison in Florida.

Outgoing Interior Secretary Deb Haaland, the first Native American Cabinet member, posted on X that the commutation ″signifies a measure of justice that has long evaded so many Native Americans for so many decades. I am grateful that Leonard can now go home to his family. I applaud President Biden for this action and understanding what this means to Indian Country.”

The fight for Peltier’s freedom is entangled with the Indigenous rights movements. Nearly half a century later, his name remains a rallying cry.

An enrolled member of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa in North Dakota, Peltier was active in the American Indian Movement, which began in the 1960s as a local organization in Minneapolis that grappled with issues of police brutality and discrimination against Native Americans. It quickly became a national force.

The movement grabbed headlines in 1973 when it took over the village of Wounded Knee on Pine Ridge — the Oglala Lakota Nation’s reservation — leading to a 71-day standoff with federal agents.

On June 26, 1975, agents went to Pine Ridge to serve arrest warrants amid battles over Native treaty rights and self-determination.

After being injured in a shootout, agents Jack Coler and Ronald Williams were shot in the head at close range, the FBI said. AIM member Joseph Stuntz was also killed.

Two other movement members and Peltier’s co-defendants, Robert Robideau and Dino Butler, were acquitted in the killings of Coler and Williams.

After fleeing to Canada, Peltier was extradited to the United States and convicted of two counts of first-degree murder. He was sentenced to life in prison in 1977, despite defense claims of falsified evidence.

Biden’s action Monday follows decades of lobbying and protests by Native American leaders and others who maintain Peltier was wrongfully convicted. Amnesty International has long considered him a political prisoner. Advocates for his release have included Archbishop Desmond Tutu, civil rights icon Coretta Scott King, actor and director Robert Redford, and musicians Pete Seeger, Harry Belafonte and Jackson Browne.

Law enforcement officers, former FBI agents, their families and prosecutors strongly opposed a pardon or any reduction in Peltier’s sentence. Democratic Presidents Bill Clinton and Barack Obama rejected Peltier’s clemency requests, and he was denied parole in 1993, 2009 and 2024.

The No Parole Peltier Association, led by former FBI agents, issued a statement condemning the action.

“There is little doubt that the President failed to understand the details of the line-of-duty killings of FBI Agents Jack R. Coler and Ronald A. Williams,” the group said in a statement. “Certainly, the President did not see the dreadful crime scene photograph.”

Former FBI Director Christopher Wray never wavered from his opposition to Peltier’s release. In a private letter sent to Biden earlier this month and obtained by The Associated Press, Wray reiterated his position that “Peltier is a remorseless killer” and said he hoped the president wasn’t considering a pardon or commutation.

“Granting Peltier any relief from his conviction or sentence is wholly unjustified and would be an affront to the rule of law,” Wray wrote.

Peltier’s supporters pushed Biden to act because Peltier is 80 and has health problems, including diabetes, high blood pressure, heart trouble and an aortic aneurysm discovered in 2016, according to his lawyers.

Peltier’s attorney, Kevin Sharp, celebrated Peltier’s commutation and insisted there was never any evidence that proved Peltier was guilty.

“It recognizes the injustice of what happened in Mr. Peltier’s case,” Sharp, a former federal judge, said. “And it sends a signal to Native Americans in Indian country that their concerns — what has happened to them and their treatment — isn’t going to be ignored. It’s a step toward reconciliation and healing.”