“Parts of our traditions kind of fall along the way if they’re not kept up,” says Veronica Sanchez-Saenz, a teacher at Irving Dual Language Academy.

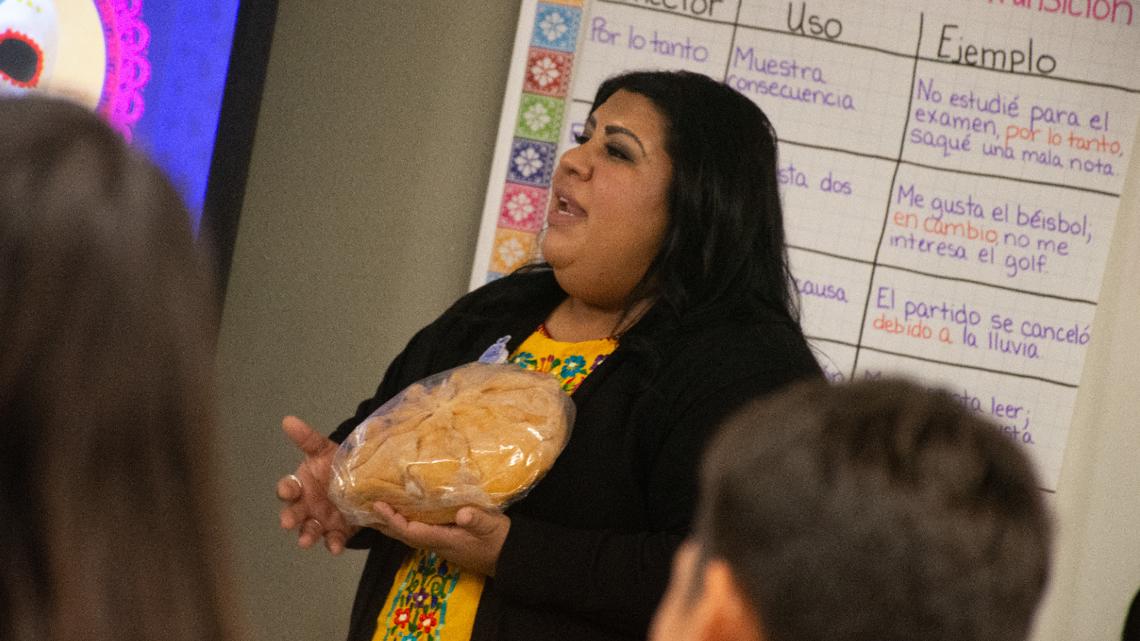

SAN ANTONIO — It’s early afternoon in Veronica Sanchez-Saenz’s Spanish class, and one of her young students is thinking about flavors.

Not from the lunch he’s recently finished, but the pan de muerto he took a bite of just moments before.

Turning over the piece of bread in his hand, he takes a stab at guessing the taste: Lemon?

Sanchez-Saenz shakes her head with a smile, and clarifies: “Orange.”

“Ahhhhh.” A wave of recognition washes over the students. This is just one taste of Dia de los Muertos culture they’re experiencing on this Monday at Irving Dual Language Academy, some of them for the first time.

For their teacher, it’s as much as about preservation as it is giving the class an introduction.

“I feel like, a lot of times, parts of our traditions kind of fall along the way if they’re not kept up,” says Sanchez-Saenz, who is in her first semester at Irving but has been in education for 12 years.

Learning about a celebration

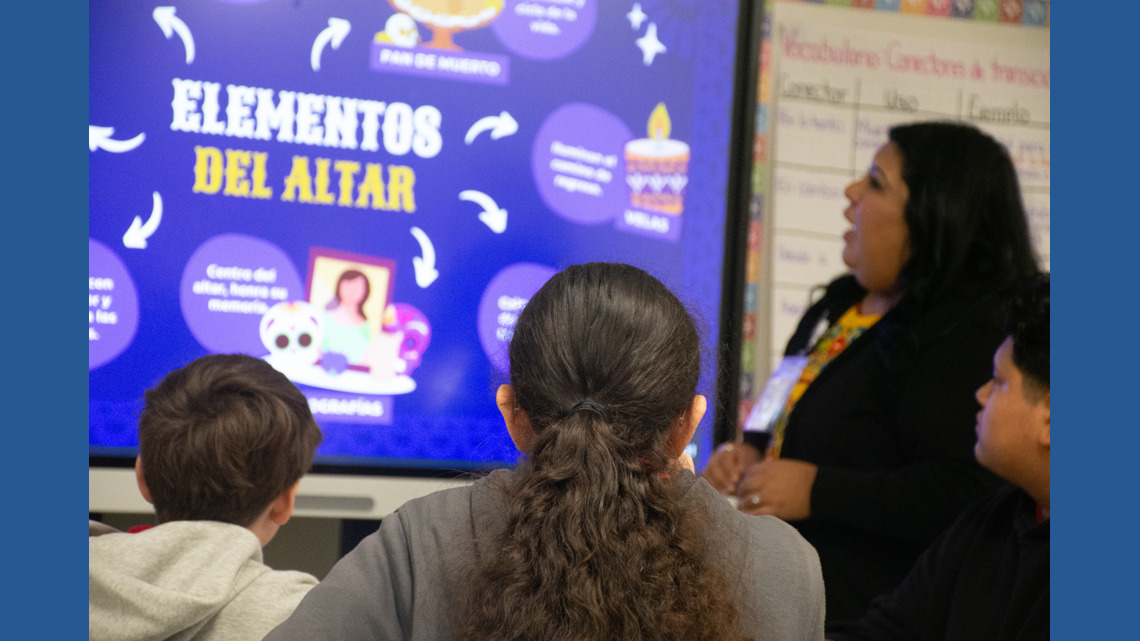

On this day, Sanchez-Saenz’s class was all about Dia de los Muertos—its indigenous origins, its traditions, its (literal) flavors. While discussing the symbolism of the pan de muerto, she took care to point to the intention behind the design baked into the bread (some students saw a flower, others a sun or a spider).

The lesson also explored more nuanced areas of the holiday, like how different regions of Mexico celebrate and the impacts of the holiday’s increasing commercialization.

At the center of it all was Sanchez-Saenz’s constant reminder: Dia de los Muertos may be close to Halloween on the calendar and flower-draped skulls might be a dominant part of its iconography, but this holiday is festive, not frightful.

“It’s more focusing on honoring the person, honoring their life, honoring who they were—looking at Dia de los Muertos, as a whole, as a celebration of life. That’s why we write the calaveras literarias,” she says, referring to the tradition of writing playful poems that make death a more approachable subject. “Because it’s satirical and making fun of something that otherwise would be morbid.”

Kamila Hernandez, a sixth grader in the class, already had an idea about the meaning behind Dia de los Muertos. Her family has honored her grandparents and great-grandparents through an ofrenda at home for the last few years, as well as visiting them at the cemetery.

She says her memories of time with her paternal grandpa are some of her strongest.

“He was very important to me,” Kamila said. “I remember, when I was little, he would always carry me and tell me jokes and we would dance together.”

As evidenced by a hallway-spanning display of colorful of ofrendas outside Sanchez-Saenz’s classroom, the curriculum actually started long before her students took a bite of pan de muerto. Irving staff organized an altar contest open to all sixth, seventh and eighth grade students; the fellow teachers who would grade them judged things like cultural accuracy, creativity, symbolism and completeness.

“There is no wrong way to do it,” Sanchez-Saenz said. “I think that’s the beauty of it—the intention is what matters the most.”

One of the winning ofrendas – featuring miniatures of soda bottles and bread, adorned with papel picado and marigolds, and featuring a photo of a smiling man wearing a hat at the altar’s top step – was created by eighth grader Mark Garcia.

The man is Mark’s uncle, who died over the summer.

“He’s the only person that has passed away in our family that I know of,” Mark said. “So I went out and bought all the things he liked, glued everything there and had a clear picture of him so we could see that it’s about him. This is my first time doing it about somebody. So it’s newer to me; it’s a different feeling.”

‘Not something to be hidden’

Sanchez-Saenz remembers learning about the specifics of Dia de los Muertos in high school, when she was introduced to the traditions and its celebratory aspects while participating in a procession as part of a folklorico group.

Today, she’s passing the traditions on through her daughter. At Irving, she says she’s found that a large number of her students, though young, are at least somewhat familiar with the aspects she’s teaching. And not just because of Pixar’s “Coco.”

It harkens back to the community served by Irving, situation on the near-west side, just a few miles away from cultural landmarks like the Guadalupe Theater.

“This campus is heavily centered in culture and tradition,” Sanchez-Saenz said. “It’s something they’ve grown up with, so that that instilled in them in some way, shape or form.”

Some of her students are from Honduras, some from Guatemala. Others are from Mexico and some speak the Afro-Honduran language of Garifuna.

“It’s beautiful to see that they learn from each other, as well… to get those conversations going is something that’s beautiful at this age. They have a better understanding of their own culture.”

PHOTOS: At this San Antonio school, students start learning about Dia de los Muertos at a young age

That’s not just the result of inclusive lesson-planning, the top administrator at Irving says, but also generational evolution. Principal Mayra Gutierrez-Ibarra, herself a daughter of immigrant parents said it was the norm for her generation to try and assimilate into the U.S.

What the school’s Dia de los Muertos celebration, contests and lessons allow students to have, Gutierrez-Ibarra says, is pride in their traditions. That’s key for a school where 90% of the students’ first language or home language is Spanish, and where a “significant” number are first-generation.

“It is very important to validate that pieces of who they are and normalize it,” Gutierrez-Ibarra said. “That’s very important, that pride. It’s not something to be hidden.”

Anyone who’s been to MuertosFest knows how large and elaborate ofrendas can get. Mark’s winning ofrenda, by comparison, can be easily carried with two hands.

Something he says he’s learned is that, no matter the scale, it’s the items and care put into an ofrenda that reflect how the person is being remembered.

He also says it won’t be the last time he makes an ofrenda for his uncle.

“This would probably be something we continue keep on doing,” he says. “Just to remember him.”