The new Texas law makes “real property theft” a crime, extends the statute of limitations, and strengthens tools to return stolen property and secure restitution.

DALLAS — For Pastor Corey Maxey, the case wasn’t just about fraud on paper — it was about losing his family’s place of worship.

His grandfather had founded the West Dallas church.

“I didn’t understand how the law did not help us out when we had documentations of who I am and all of that,” Maxey said.

And the fraud, he said, was carried out by someone who called himself a pastor.

“When we called the police out, police told us we had a civil situation,” Maxey recalled.

In 2017, Pastor Whitney Foster transferred ownership of the church from Maxey’s congregation.

“It scattered my congregation. And so, it kind of broke us up,” Maxey said.

Cases like Maxey’s — highlighted in WFAA’s Dirty Deeds series since 2019 — helped push for a new law known as S.B. 16. The law passed during the most recent special session. It was signed into law Wednesday by Gov. Greg Abbott.

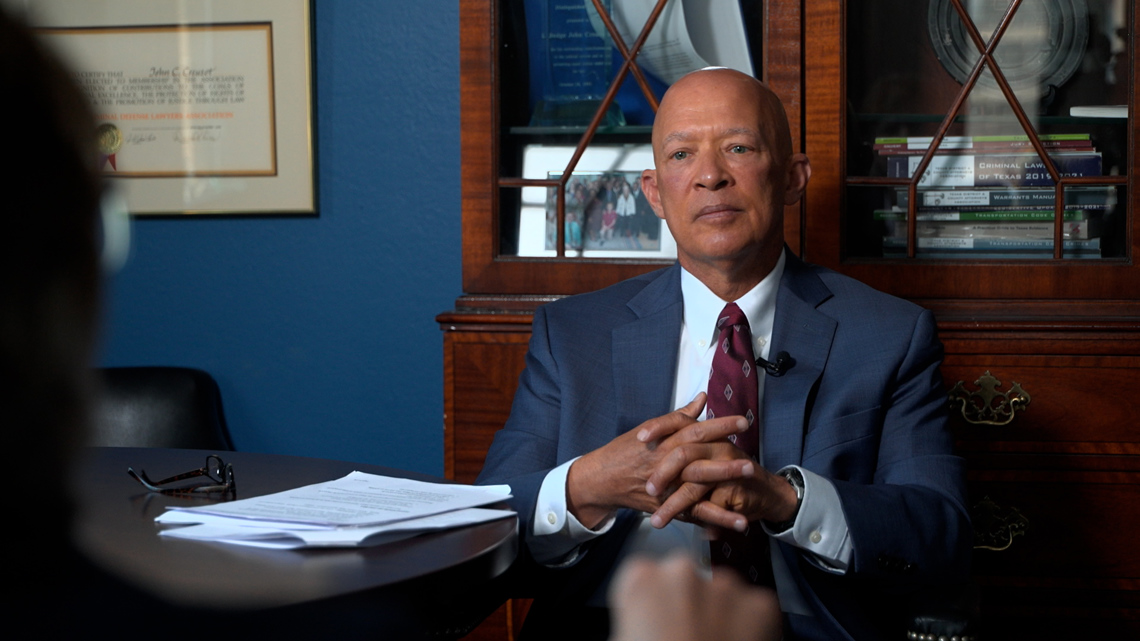

“In the past, law enforcement thought this was purely civil,” said Dallas County District Attorney John Creuzot, whose office played a key role in drafting the bill’s language. “What we’ve done is rearranged all of these statutes and made it much more clear that it’s a criminal case — easier to prosecute, easier to get restitution, easier to make a person whole.”

The law, authored by state Sen. Royce West, creates a new crime called “real property theft” with stiffer penalties and doubles the statute of limitations from five years to 10 years. It also requires judges to include property addresses and legal descriptions in sentencing orders, and it gives the state new tools to pursue restitution for victims.

If a defendant still holds title, they can sign a quit claim deed returning the property as part of their restitution.

“It allows a victim to take that document to a civil court as evidence that there was fraud … and ask the court to nullify them, or declare them void or fraudulent,” Phillip Clark, an assistant Dallas County prosecutor who specializes in prosecuting deed fraud cases, said during a press conference last month.

Because it’s now its own crime category, police and prosecutors will also be able to track how often deed fraud occurs.

“It is going to empower victims to get restitution and to unwind these frauds that they’ve been a victim of,” said state Rep. Rafael Anchia, who was one of the sponsors of the legislation.

Lawmakers had already given some county clerks the ability to check photo IDs before ownership changes could be filed in person. The new law strengthens that — now all clerks must check and keep copies of IDs for deeds filed in person, giving investigators crucial tools when deed fraud is discovered years later.

Most of S.B. 16 takes effect Dec. 4, according to Rep. Anchia’s office. But beginning Jan. 1, county clerks must provide law enforcement with a property’s location and the filer’s ID if someone reports a fraudulent document.

It’s the latest in a slate of laws helping to prevent fraud.

In the regular session, a new law allowed property owners to ask a judge to void fraudulent deeds without paying filing fees, making it easier and more affordable for victims to regain title of stolen properties.

Another law required notaries to receive training, maintain records for up to 10 years, and makes it a crime to notarize a signature for someone not present — a common issue in deed fraud cases.

A third measure gave county clerks the authority to reject suspicious property filings, request documentation and notify affected parties. Previously, clerks lacked the explicit authority to deny questionable filings.

Those laws took effect Sept. 1.

“I am glad that there’s something like that now so that way it can help prevent further deed theft… because there are a lot of people out here that are just taking advantage of people,” Maxey said.

Maxey told WFAA that back in 2015, his congregation was in the middle of remodeling the church. They had temporarily relocated while repairs were underway. That’s when they discovered Foster and his followers had moved in and set up shop inside the building.

Court records show Maxey tried to have Foster and his congregation removed for trespassing. But Maxey said the judge told him the matter was outside the court’s jurisdiction.

Without the money to fight a lengthy legal battle, Maxey said his congregation had no choice but to move on.

But he did testify at Foster’s trial last year.

“What was done in the dark had finally came to the light,” he said.

Foster is now serving a 35-year prison sentence for stealing three churches, including Maxey’s.

Today, with new homes going up all around, Maxey’s former church sits on prime land.

“So do you want this building back?” he was asked.

“Hey, if I can get it back we can still do great things even in the mess that it’s in,” he said, referring to the rundown state of the building. “I believe that God can do anything.”

Maxey has since started a new congregation. He just doesn’t have a building.