The community museum is housed in the former Ruben’s Ice House and was planned by a team of historians, organizers, archivists and artists.

SAN ANTONIO — It was mere moments after leaving the newest addition to San Antonio’s historic west side when Rita Garza made a decision: She would contribute to it.

“I’ve got things at home I’m gonna go ahead and give to (staff) to put in there,” Garza said. “A can of Pennzoil, tin cans. I’ve got a Budweiser billiard light – old – and I always thought I could sell it. It’s better here.”

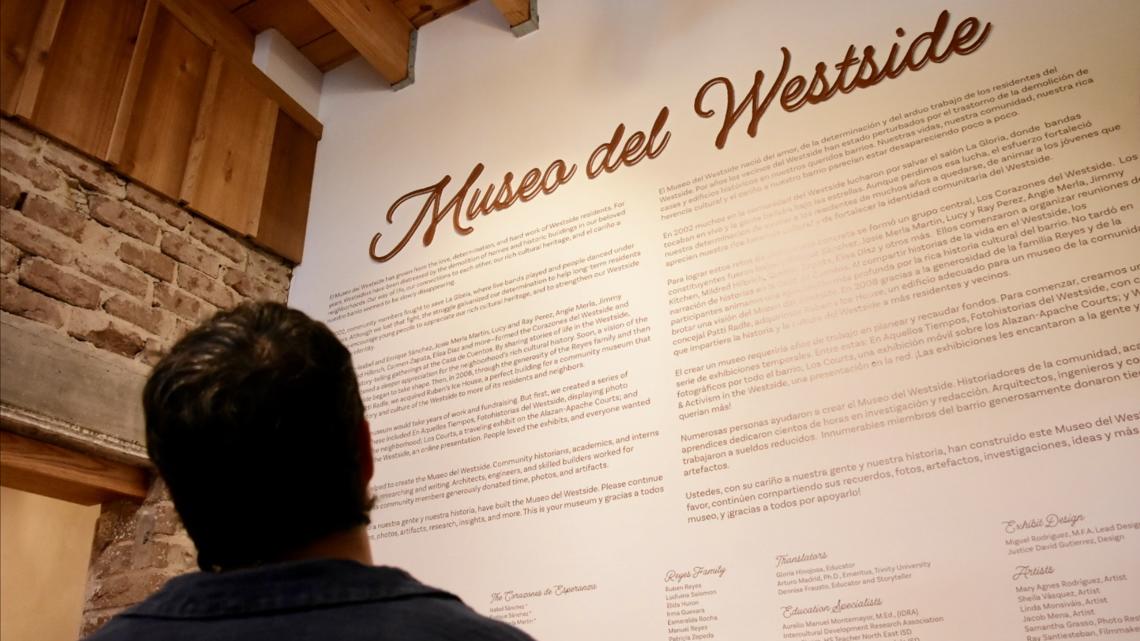

The “here” referred to by Garza, a 58-year-old Lanier High School graduate who was born and continues to live on the west side, is the Museo del Westside—a brand new community museum that debuted along South Colorado Street on Saturday, the culmination of years of planning involving curators, historians, community organizers, archivists and artists.

To a passerby, the items Garza listed off as things she wants to donate to the Museo, located at Rinconito de Esperanza (the South Colorado Street hub of the Esperanza Peace & Justice Center) might have seemed trivial. A leading tenet of the museum, however, is that no detail of life in this part of the city – a largely Mexican-American community, and one of San Antonio’s economically poorest – is too small to preserve. Taken as a whole, they create a diverse collection of interactive exhibits Garza says she found “overwhelming” to explore firsthand.

“We know that we thrive when we prioritize preservation, community and investment in our most vulnerable,” City Councilwoman Teri Castillo, who represents this part of San Antonio, said at the Museo’s opening ceremony. “I’m grateful to be here in community with folks who share that vision and that.”

The Museo is really just the first step of the Rinconcito de Esperanza $3.1 million next chapter, one that also includes the reconstruction of nearby homes.

A long-awaited vision

The Museo was envisioned as a place where stories can be shared and history can live on. That’s true right down to the building itself, which decades ago used to be Ruben’s Ice House, a notable bar and hangout spot owned by the Reyes family.

About 20 years again, the family had a choice to make: Sell it to a developer that would tear it down, a fate met by so many nearby historic buildings, or to the Esperanza Peace & Justice Center, which would preserve it.

The Esperanza acquired it. A dream took root.

But, as an introductory message just inside the doors of the Museo del Westside explains, “creating a physical museum would take years of work and fundraising.”

Working with then-City Council members, the organization fought about a decade ago to receive $1.5 million in reimbursable dollars for the project through the West Side TIRZ, allowing tax dollars to flow to the effort.

But the Esperanza still had to secure a number of grants to actually pay for the project, and a huge assist arrived when the Mellon Foundation – realizing it wasn’t giving enough money to Latino organizations, Sanchez says – provided $1.6 million.

‘Smithsonian-quality’ aspirations

Eventually, in the spring of 2022, the Esperanza broke ground on renovating what was once Ruben’s Ice House—beginning the building’s evolution from one kind of community hub to another. At the same time, the Esperanza, working with dozens of collaborators, starting gathering records, information and artifacts that could be displayed.

“Some of these are from other museums and archival (spaces) and they’re just in storage. It was really, really important for us to bring everything out,” said Laura Hernandez Ehrisman, a historian who sat on the planning committee and helped curate Museo del Westside. “They have not been presented in those spaces as often as you think they should.”

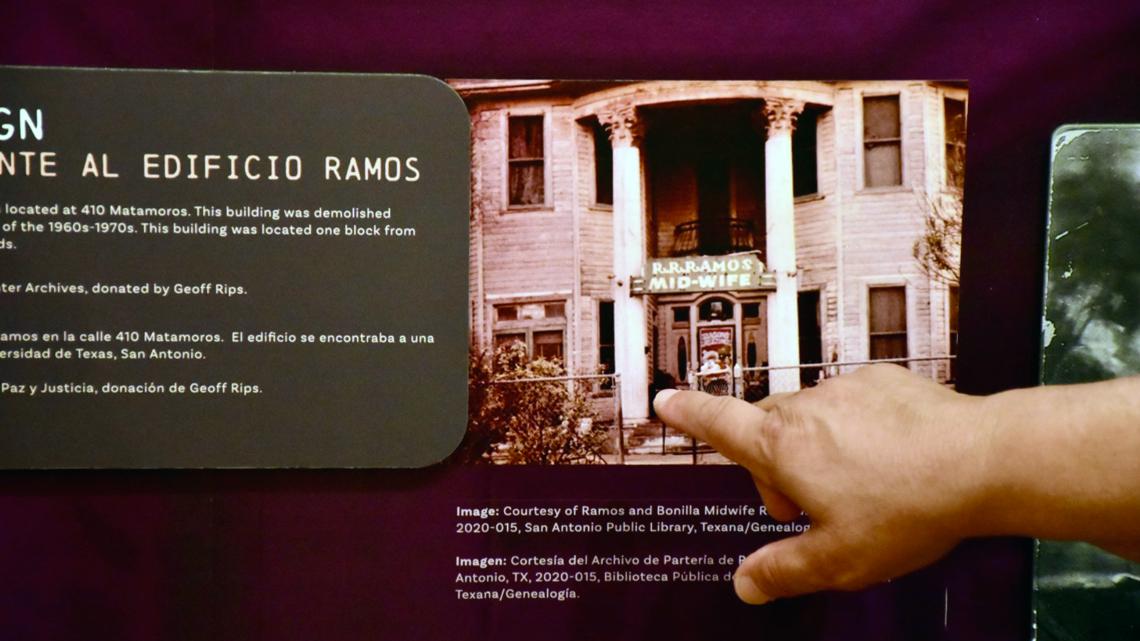

It’s one thing to gather all those items – among them residential records, singers’ gowns, a midwife business sign and a barbershop chair on loan – and another thing to design the space to display the space as much as possible. After all: This was built to be an ice house, not a museum.

“It’s like a puzzle,” said Miguel Rodriguez, a contemporary artist who teamed up with Justice David Gutierrez to design the exhibit spaces. “I really just wanted to present something to the west side community that is Smithsonian-quality.”

This being Rodriguez’s first time designing an exhibit space, he says he learned plenty. But he was also able to utilize his visual art experience to create interactive elements for Museo del Westside; walk through the museum and you’ll come across rotating wheels jutting out of wheels that share west-side history, oral histories of the family that owned Ruben’s, a wall to closely examine the neighborhood through different kinds of maps, and a huge grid of streets where visitors are welcome to pin where they lived, went to school or attended church.

“History has always been a very intimate action within our families,” said another of the museum’s curators, Veronica. “Our love for history is always there, and to see people come out and see history live at a museum, it’s like taking the private to a very public place.”

Now, 19 years after an initial street exhibit in the form of west-side ancestors’ photos were first displayed along the road, the Esperanza has a new way to share the neighborhood’s stories—of its people, its heritage, its triumphs and struggles.

Some of that history is born out in detailed histories of trailblazers like Lydia Mendoza and Jovita Idar; elsewhere, a recreation of a corner store has old cans of Folgers coffee grounds and burlap potato sacks to transport visitors back to their family homes. The west side’s strong history of fighting for labor rights is also on proud display.

In the corner of another exhibit sharing the stories of famous female musicians who lived in San Antonio sits a donated pair of flamenco icon Teresa Champion’s ruby-red dance shoes—giving visitors an intimate experience with detail that curators say can’t be captured in a digital archive.

“That’s what objects do, they build those connections,” Veronica said. “Even if you’re not a folk dancer, you’ve seen them, and you’re like, ‘Oh my god, I didn’t know they had nails on the bottom.’ You can’t beat having the objects displayed.”

PHOTOS: Museo del Westside opens in San Antonio

Holding on to history

A common theme emerged in the remarks by politicians invited to speak at Saturday’s opening ceremony, including Castillo, Congressman Joaquin Castro and Mayor Gina Ortiz Jones: the importance of highlighting the community and its successes through storytelling.

That’s partly what the Esperanza Peace & Justice Center has been doing since 1987. It’s also advocated on behalf of and empowered the people of the west side. MujerArtes, one of its longest-running programs, for instance, makes claymaking accessible to women who typically may not be able to unleash their creativity.

By sharing stories of the past through Museo and other initiatives, the group hopes it can continue the group’s mission of strengthening west-side identity. Gloria Colom Braña, a cultural historian for San Antonio, refers to it as “cultural consistency.”

“It’s not just about, ‘Let’s maintain music and recipes and traditions and the cultural knowledge of the tienditas and the stories of our ancestors,’” Braña says of Esperanza’s efforts. “It’s also, ‘Let’s physically keep people in their houses.’ That really is part of the strength of the community.”

The impact was glimpsed Saturday with neighbors who visited beyond the streets and yards that make up this part of San Antonio. Among those waiting to enter the museum for the first time, a crowd that included children and abuelos alike, was Frank and Teresa De Leon; they don’t live on the west side, but when they moved to the Alamo City from Los Angeles in 2005, they found a familiar atmosphere there.

“The restaurants, the panaderias, the culture, the music—it’s what we relate to,” Frank said, calling the museum a “powerful” new marker of the west side. “The fact that they’re opening it up to everybody and just holding the culture together, keeping it alive, bringing people together…. that way, the next generation can hold on to their roots.”