Bankruptcy records show at least ten “forever” prize winners may never collect millions they were promised.

PORTLAND, Ore. — For decades, Publishers Clearing House made dreams come true. In August 2012, its Prize Patrol surprised a Southern Oregon man with balloons, flowers and an oversized check.

“You won $5,000 a week, forever!” a member of the Prize Patrol said with TV cameras rolling.

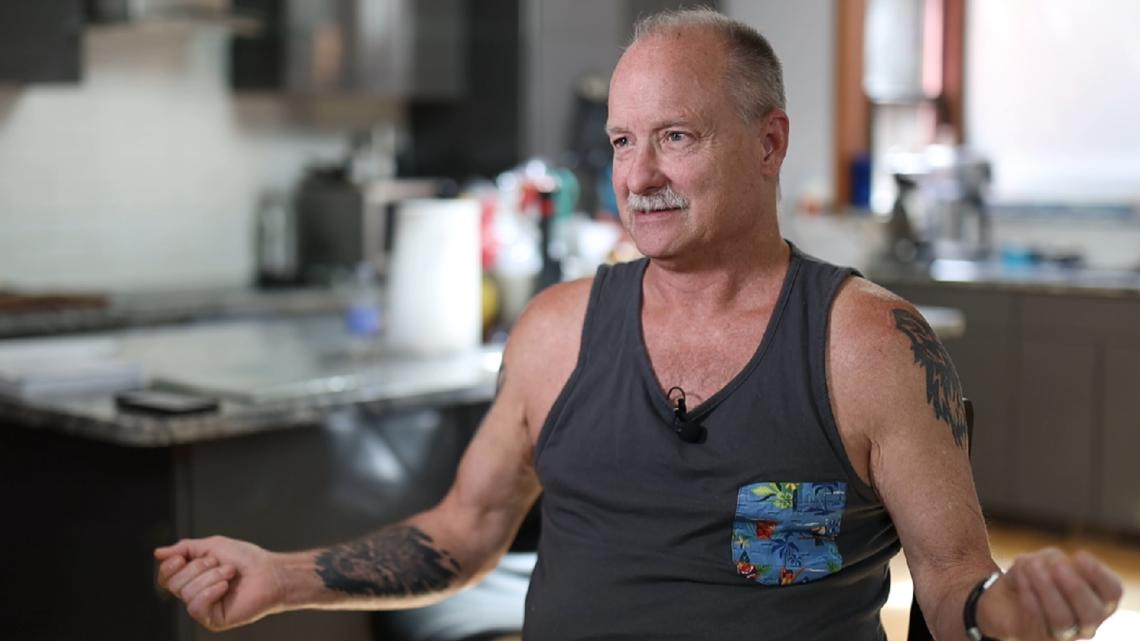

John Wyllie of White City, Oregon thought he was set for life. The jackpot allowed him to retire. Wyllie moved closer to his kids and bought a house on six wooded acres near Bellingham, Washington.

Every January for the past 12 years, Publishers Clearing House deposited a prize payment of $260,000 into Wyllie’s bank account. But this year, the money never came. In April 2025, Publishers Clearing House filed for bankruptcy.

“Why didn’t somebody give me a heads up? ‘Hey, we’re going out of business,’” Wyllie asked. “It’s not a good way to treat anyone.”

A KGW investigation found that at least ten past Publishers Clearing House prize winners haven’t been paid, and a bankruptcy expert says they probably won’t get their millions after the company went bust.

“This feels like a nightmare,” Wyllie said. “I thought this was going to go on for the rest of my life, so I didn’t really have to worry about money.”

Now, he worries a lot. The annual prize payment was his only source of income. The bills are piling up. The 61-year-old has had trouble finding a decent paying job after being out of the workforce for so long.

“I sold my jet ski. Sold my trailer. I had a little bit of money left over and that’s what I’m living on right now,” Wyllie explained. “Pretty sure I’m going to lose my home.”

Some forever prize winners say they’re also dealing with the emotional toll of hitting the jackpot, then having it taken away.

“You change people’s lives, and now, you messed it up,” said Tamar Veatch.

In February 2021, Publishers Clearing House showed up on Veatch’s doorstep in Cottage Grove, Ore., with balloons, a big check and a promise: $5,000 a week for the rest of her life.

Earlier this year, when the annual payment didn’t arrive, as it had for the past four years, Veatch and her husband Matthew contacted Publishers Clearing House. A representative told them the payments would resume on a quarterly schedule. Then, the company filed for bankruptcy.

“It’s unfortunate there was no warning,” said Matthew Veatch. “The big letdown for me is that we trusted them.”

The Oregon couple, both disabled Army veterans, had to suddenly reshuffle the family budget. They have three kids and a mortgage to cover.

“It’s real tight,” explained Matthew.

The couple relies on their disability payments from Veterans Affairs to pay the bills, and they get some help from a roommate. But they’ve canceled all travel plans and can no longer afford to help friends with unexpected emergencies, like a broken-down car or sick pet.

“We were fine before, but it opened a lot of doors for us, like fun stuff to do with the kids; we were able to travel,” said Veatch. “Now, we’re back to where we were.”

Bankruptcy records show Publishers Clearing House has at least 10 unpaid prize winners. Most are owed more than $2 million.

University of Oregon law professor Andrea Coles-Bjerre said in bankruptcy proceedings these prize winners join the list of unsecured creditors.

“There’s just not enough money to go around to pay everyone,” said Coles-Bjerre. The law professor thinks it is unlikely that the past winners will get their prize money.

“Here, we have a really, really bad situation,” explained Coles-Bjerre. “You can’t get blood from a stone.”

Some winners did get paid before bankruptcy.

Publishers Clearing House offered forever prize winners the option of annual payments or a lump sum.

“It worked out pretty good,” said Ricky Williams. In August 2019, the Prize Patrol surprised the Prestonburg, Kentucky, man with the Clearing House jackpot of $5,000 a week for life.

Instead of annual payments, Williams chose the lump sum, collecting more than $3 million. “If I’d been 20 years younger, I would have taken the payments,” said the 71-year-old.

In July, ARB Interactive bought Publishers Clearing House out of bankruptcy. A spokesperson said it will keep running contests under the Publishers Clearing House name.

“We understand the concerns surrounding unpaid prizes owed to past winners and are taking decisive steps to ensure that every future prize winner can participate with absolute confidence,” the spokesperson wrote in an email.

ARB added it will only pay out prizes awarded after it took over.

“We recognize the impact this has had on past winners and the disappointment caused by the bankruptcy process,” the spokesperson wrote.

So how did this happen to an American institution like Publishers Clearing House, the direct-mail marketer of magazine subscriptions and merchandise known for its Prize Patrol?

“You can’t be a sweepstakes company and not pay your winners,” said Darrell Lester, a retired company executive and author of “Downfall of an Icon: The True Inside Story of Publishers Clearing House.”

Lester said the company used to protect winners by setting aside the money up front in secure bank or insurance accounts.

“I know for a fact in my day; there was a 30-year annuity that was prepaid in the winner’s name,” Lester explained. “Something changed.”

Publishers Clearing House did not respond to KGW’s request for comment.

In April, the Federal Trade Commission announced a settlement requiring Publishers Clearing House to pay $18.5 million to nearly 282,000 consumers over misleading claims. Regulators said the company deceived people into believing they could not enter into the sweepstakes without purchasing a product or that their chances of winning would be increased by purchasing products.

Forever prize winners were supposed to be paid weekly for the rest of their life. Then, after they die, the weekly payments were to continue for a recipient of their choosing.

For John Wyllie, that gift was supposed to go to his son.

“That was something I wanted to leave for him,” said Wyllie.

Looking back, the 61-year-old is grateful for the experience. He collected six-digit prize payments for more than a decade. Wyllie just wishes he had time to prepare for the lost income and the broken promise.

“I was proud of the fact I left my children something,” Wyllie said. “Now, I can’t leave them anything, and it really disappoints me.”