While historians and social justice advocates can acknowledge the gaps in the public education system in San Antonio, and across Texas on a larger scale, there’s more to the story. In fact, there are multiple stories missed and forgotten throughout history.

In the 1954 U.S. Supreme Court ruling of Brown v. Board of Education, segregated education was outlawed across the country. Given resistance in some states, the implementation of this change was not immediate across the U.S. Still, Texas was actually one of the Southern states to lead the pack toward desegregation. One local district has even been noted in the history books as an early standout in the matter.

San Antonio Independent School District, or SAISD, was one of the first districts in the country to comply with the Supreme Court ruling, though Black students were already welcomed and attending the then-named San Antonio Tech High School in 1954. The integration process began during the 1955-56 school year and was made easier by “good race relations and an articulate policy statement,” as noted by researcher and author Anna Victoria Wilson in the state’s historic archives.

Despite SAISD’s notable place in history, the Alamo City’s public school districts have collectively been called out for, perhaps unofficially, resegregating students and creating an imbalance of educational resources and opportunities among students living in the same city. The redlining of local districts by income, which often lines up with race, has led to a concerning educational gap between students from San Antonio’s Southside and Westside versus the Northside and in wealthier communities like Alamo Heights and Boerne.

Though the implementation of desegregation was slow in other Texas cities, such as Houston, Texas still comprised some 60% of desegregated school districts in the South in 1964, an entire decade after the Brown v. Board of Education ruling. In the present day, Texas leadership is not as much a leader in progressive policies, instead pushing against what’s been broadly labeled ‘critical race theory’ in the classroom.

In 2021, Gov. Greg Abbott signed a bill limiting how Texas public school teachers can discuss current events regarding race, as well as how they teach the history of racism in the U.S.

So, how about a quick, insightful history lesson before the end of Black History Month.

Black Texans seek education after emancipation

Prior to the official integration of public schools, Black Texans did have an education system of their own, one that came after slavery was outlawed in 1865. That same year, the U.S. Congress created the Freedman’s Bureau, which oversaw the education of the Black population in many states, including Texas.

At the beginning of 1866, Texas had 10 day schools and six night schools serving a total of 1,041 Black students. By July of that year, there were 90 schools and nearly 4,600 students, Wilson found. The program continued to grow with the number of Black teachers increasing over time.

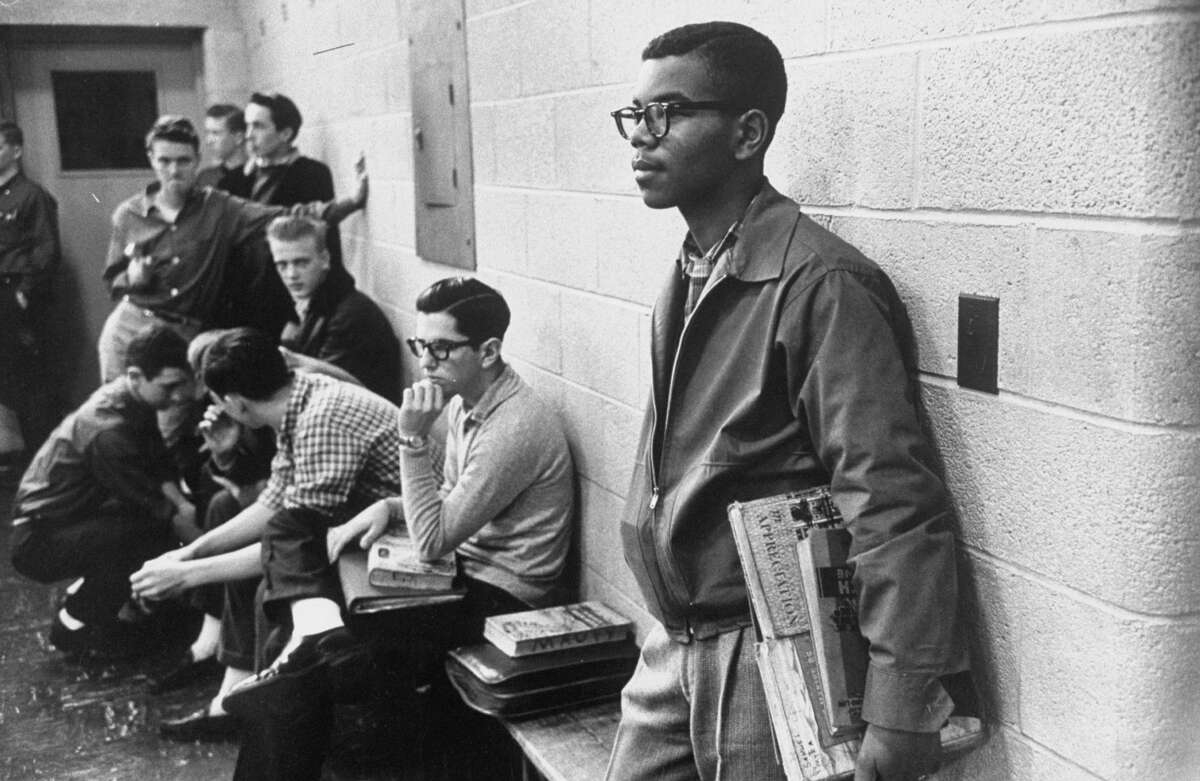

Lewis Cousins (R) only African American student in newly desegregated Maury high school standing alone. (Photo by Paul Schutzer/The LIFE Picture Collection via Getty Images)

Paul Schutzer/The LIFE Picture Collection via

By 1871, however, Texas organized the official public school system, which led to the push for Black schools in San Antonio. The Rincon School for African Americans opened that same year and had an enrollment between 100 and 170 students over the next few years. In 1888, an Irishwoman named Margaret Mary Healy Murphy opened St. Peter Claver Colored Mission, the city’s first Catholic school for Black students.

Up until then, there was not a high school for Black students in San Antonio despite calls for such over the years. Philanthropist and businessman George Washington Brackenridge answered this call by donating funds and supplies to expand the curriculum available at the Rincon School in 1889.

In 1902, a former school founded by the Episcopal Church was turned into a junior college and vocational institute now known as St. Philip’s College. The Rincon/Brackenridge school moved into a larger building on the Eastside in 1915 and was renamed the Frederick Douglass Colored High School.

Challenges to Black education and livelihood

Though Black San Antonians had access to an education, there were still major setbacks and gaps. In 1915, San Antonio public schools had an enrollment of 21,983 students, according to archives from the University of Texas at San Antonio. Black students, however, made up just 9.3% of these students.

There was still an imbalance in 1938, when there were just four elementary schools, 10 middle schools, and one high school for Black students among the 67 public schools across San Antonio. With 38 Catholic schools at the time, only two admitted Black students.

Finances also disrupted local Black schools, some of which didn’t have running water. Issues of money at St. Philip’s College led to a strike by five of the seven faculty members in 1932. Despite the campus being small, the strike impacted 75 students and was a blow to the community as St. Philip’s was a symbol of achievement to the Eastside.

As for San Antonio’s public school system, financial problems resulted in the accreditation loss for Phillis Wheatley High School, the Black high school that opened the previous year.

Black public schools were first surveyed in 1921, finding that there were 6,369 Black students across Texas. Through the 1930s, Black schools’ average school term was four days shorter than that of white schools. However, Wilson wrote Texas spent about a third less toward the education of Black students. The researcher also found that Black teachers were paid 28% less than white teachers.

As many may already know, the inequality between the Black community and the rest of the population was felt beyond the classroom. Though the South is regarded as the epicenter of the Civil Rights Movement, San Antonio had its own key moments during the era.

The Civil Rights Movement in the Alamo City

San Antonio desegregated all city facilities, including parks, golf courses, and tennis courts, in 1954 following a lawsuit from the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, or the NAACP. Though these facilities were open to all races, the move came after Black teenagers attempted to swim at a Northside pool where only white residents were welcome. Black residents were not permitted to enter city-owned swimming pools until March 1956.

And despite this victory for local Black residents at the time, segregation remained intact at privately-owned facilities and businesses.

The Youth Council tied to the San Antonio chapter of the NAACP sent letters to Joske’s, S.H. Kress, and Woolworth on March 7, 1960 calling for change. At the time, the now-closed department stores banned Black individuals from eating at their dining facilities. Archives from the San Antonio Public Library system share the letter, signed by Youth Council president Mary Lillian Andrews, with San Antonians today:

“Youth of all races in San Antonio go to school, ride the buses, enjoy municipal recreational facilities together, but they cannot eat together in your store. Help the youth of San Antonio realize that the principles stated in the Holy Bible and the Constitution of the United States can be a living reality in San Antonio by abolishing this discriminatory practice in your store. We feel the citizens of San Antonio are intelligent enough to accept such change.”

The following day, the Youth Council sent letters to other department stores, requesting responses from each of them. Since no responses came in the following days, the Youth Council held a rally at the Second Baptist Church on March 13, preparing for sit-in demonstrations later in the week.

On March 16, 1960, demonstrators headed to the Woolworth department store at Alamo Plaza to do just that, inspired by a sit-in at a Woolworth store in Greensboro, North Carolina, the month before.

Black shoppers were usually served their food to-go at the time, but the demonstration included peaceful protesters taking turns asking for service at the “whites-only” counter. Police were on stand-by at the store while wait staff, as well as white patrons, reportedly used racial slurs against the Black residents. Despite a degree of commotion, and unlike the Greensboro sit-in that turned violent, some San Antonio lunch counters began serving Black patrons immediately after.

Desegregation begins and continues

While Black San Antonians gained access to education and public spaces over the decades, the community’s fight is far from being over. The city was collectively progressive during the 1950s, technically ahead of much of the nation in terms of integration at the time, but there is still much work to be done.

A newspaper clipping from the San Antonio Register shows a September 1, 1955, article on integration in Bexar County. Online archives indicate that other local school districts were early leaders for desegregation, with East Central ISD, Edgewood ISD, Harlandale ISD, Lackland ISD, La Vernia ISD, Randolph Field ISD, Schertz-Cibolo ISD, and South San Antonio ISD all at least beginning the integration process by 1956.

Yet, students of all races in these same school districts still experience forms of racism, whether obvious or not, today. Redlining in San Antonio, which impacts residents in every aspect of their life, has determined where these students go to school and thus the resources they have access to, the opportunities available to them, as well as how they’re perceived. In San Antonio, where strangers default to asking what high school you attended, that’s dangerous.

While the Alamo City can take pride in the strides it has made in the past, let this history lesson be a reminder that there’s still an ongoing fight for equality.