The U.S. Senate unanimously approved a bill to exhume Fernando Cota, a convicted rapist suspected in the murders of at least six women.

SAN ANTONIO — An alleged serial killer could soon be exhumed from a San Antonio cemetery after the U.S. Senate unanimously passed legislation from U.S. Sen. John Cornyn (R-TX) to dig up the remains of Fernando V. Cota, a convicted rapist suspected in the murders of at least six women.

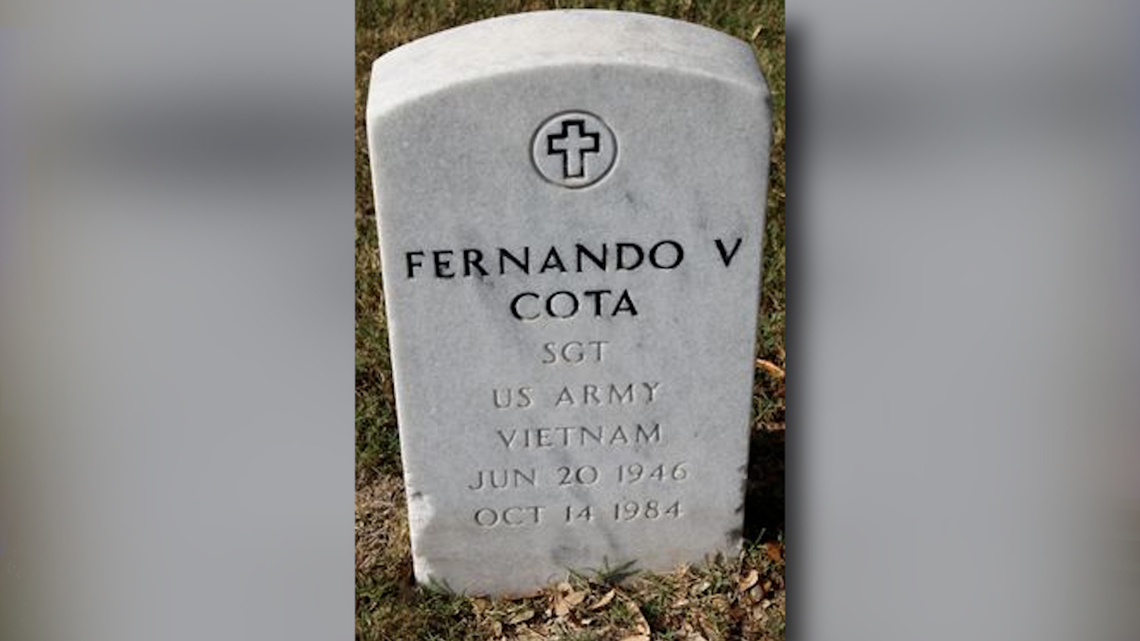

Cota is buried at Fort Sam Houston National Cemetery, a final resting place meant to honor America’s war heroes.

“Fernando Cota faced multiple sexual assault and rape allegations and was the prime murder suspect for half a dozen women after his transition to civilian life,” Cornyn said in a statement. “While current law prohibits such a disreputable person from receiving the high honor of being buried amongst those who valiantly served our nation, my legislation would correct this oversight and ensure Cota’s remains are no longer beside those who lived lives worthy of memorial at Fort Sam Houston.”

Sen. Ted Cruz (R-TX) is co-sponsoring the measure, which now heads to the U.S. House of Representatives.

Cota, originally from Texas, was drafted into the U.S. Army and served in the Vietnam War. After returning home, he faced multiple sexual assault allegations and in 1975, was convicted of binding and raping a nurse. He served just eight years of a 20-year sentence before being paroled in 1983.

Within a year, police in California say he was suspected in a string of brutal killings in the San Jose area. In October 1984, officers stopped Cota for erratic driving. He shot himself before he could be arrested. Inside his van, police found a wooden box containing the body of 21-year-old Kim Marie Dunham, who had been reported missing the day before.

A search of his apartment revealed a closet where investigators believe victims were tortured. Detectives also found fake IDs, a false police badge, women’s clothing and personal effects, along with advertisements Cota allegedly used to lure young women by offering rooms for rent near San Jose State University. Six women were ultimately linked to Cota — all killed by strangulation, stabbing or blunt force trauma.

‘She was there, then she wasn’t’

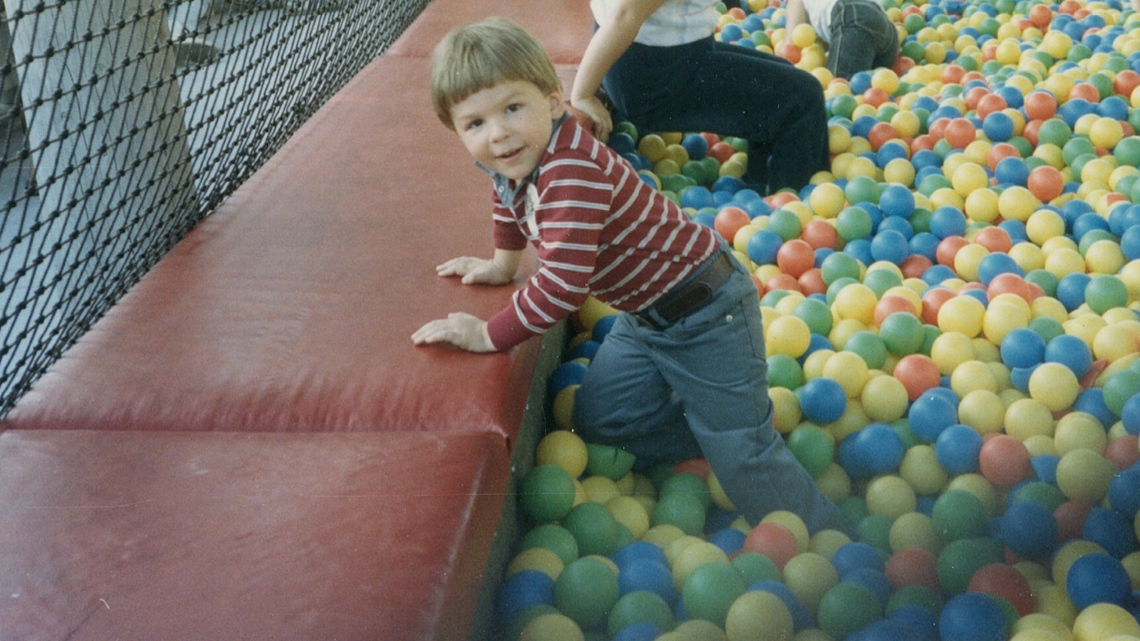

One of those women was Teresa Linda Sunder. Her son, Dave McCausland, was just 5-years-old when she was killed.

“All I can really remember is she was there, then she wasn’t there,” McCausland said.

For more than a decade, he was told his mother died in a car crash.

“When my mother died, I was told it was a car accident by my father,” he said. “My whole life has been focused on that one question: What happened to my mom?”

McCausland says his mother struggled at the time.

“It wasn’t the best of times living in California,” he said. “My mother was a drug addict, she was a prostitute struggling through a custody battle with my father.”

In his 20s, he learned the truth from an uncle.

“Everybody tells me my mother wasn’t murdered. They say it was a car accident. Police say it was this guy. And my uncle says, ‘Oh no. This goes way deeper than that,’ and he told me about Fernando Cota.”

The discovery that changed everything

In February, while researching his mother’s case, McCausland learned something infuriating — her alleged killer was buried at Fort Sam Houston National Cemetery.

“I was angry. I stared at my screen. I wanted to smash my computer,” he said. “We cannot allow these predators and monsters buried among heroes.”

That’s when he launched a petition and proposed “Teresa’s Law,” urging Congress to act.

“We’re not only trying to dig Cota out of the ground,” McCausland said. “We’re trying to change history. We’re trying to make sure this never happens again for any reasons.”

He reached out to both the House and Senate Committees on Veterans Affairs, alerting them to the discovery and pushing for legislative change. Along the way, he says, he learned that other veterans with serious criminal records are buried in national cemeteries.

On Aug. 1, the Senate voted unanimously to approve Cornyn’s bill.

“Unanimously, everybody in the Senate voted yes to pass it. I couldn’t believe it,” McCausland said. “How could anybody feel this is okay?”

McCausland says the fight has consumed his life.

“At 47, I should be living a life. Honestly, I don’t have a life. All I do is this,” he said. “This whole quest to find the truth wasn’t just for me. It’s for those women as well.”

A podcast rekindles the case — and family ties

For true crime podcaster Esther Ludlow, the Cota case came back into focus when a local business invited her to present on a murder that happened in Campbell, California — a small town outside San Jose.

“I came across this one and got all the details about how much of it was so local to San Jose and the surrounding area,” Ludlow said.

She’s been podcasting for nine years, covering more than 350 episodes — each full of twists and turns. But Cota’s case, she says, felt different.

“He’s kind of a ghost. We don’t know hardly anything about him,” Ludlow said. “Even his victims, I had a hard time finding information. I was trying to make these people — so people will know these are real people that this happened to because it was in and out of the news so fast.”

Her deep dive included rare details about the killings, his methods and the aftermath — information even McCausland had never uncovered.

“It just blows me away that that podcast [episode] even exists,” McCausland said. “I was watching it and I go, ‘Oh my gosh.’ All the memories just flooded back.”

In a twist worthy of one of Ludlow’s episodes, the story also reconnected McCausland with his long-lost sister, who commented on the episode online.

A rare move in U.S. history

If the House passes Cornyn’s bill, it would mark only the third time Congress has ordered a disinterment from a national cemetery. There is precedent: Andrew Chabrol, executed for murder, and Michael Alan Silka, killed after a spree shooting in Alaska, were both posthumously removed through acts of Congress.

For McCausland, this is about more than one man’s burial.

“We’re not only trying to dig Cota out of the ground. We’re trying to make sure this never happens again,” he said. “Many people have heroes buried in national cemeteries. What if there were more?”